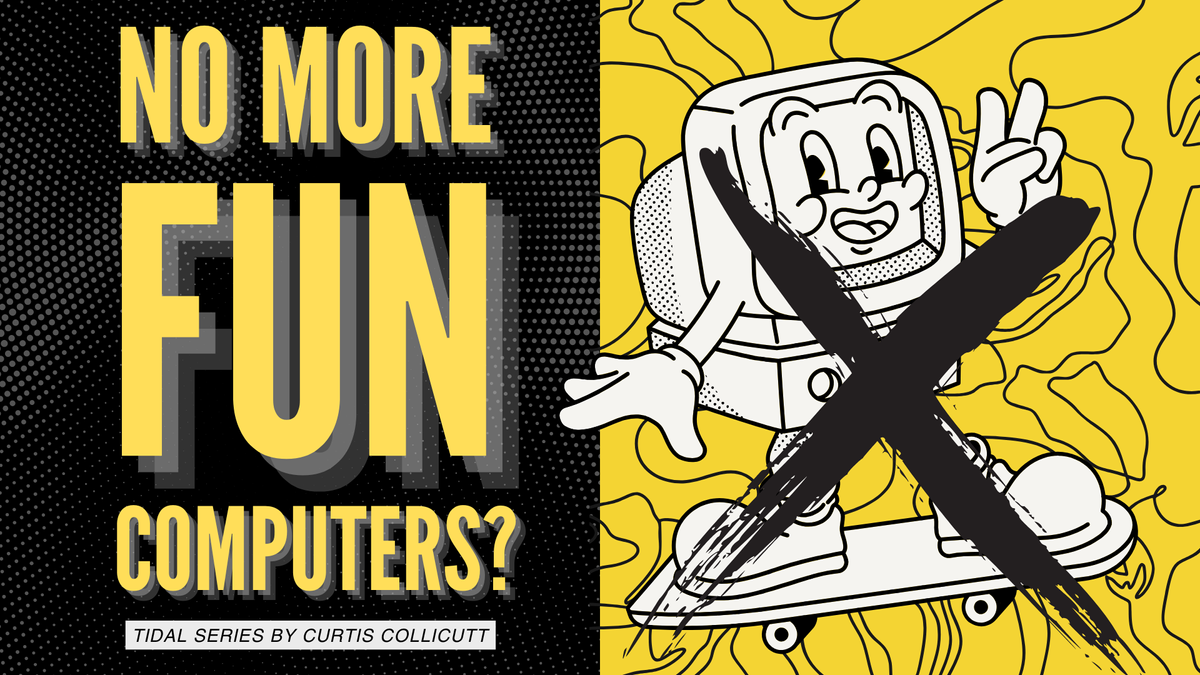

No More Fun Computers?

The contrast between late 90s transparent tech (iMac G3, VW Beetle) and today's opaque AI systems reflects a cultural shift from optimistic, visible computing to inscrutable black-box technology. However, AI could ironically help make computing more natural and "invisible" again.

The Era of Transparent Computers and Products

Transparent, see-through, bright and fun computers were all the rage in the late 1990s, but they weren't just things, they were symbols of optimism. Hundreds of transparent looking consumer products were launched. We liked them, and we bought them.

Looking back, people–and things–just seemed happier back then, the salad days between the fall of the Berlin Wall and 911, when we were more willing to believe that good things would come from computers and computer systems, so much so that we even thought we could understand them, in a way, just by looking in at the underlying circuitry. Yes, there it was–the fun computer. Not entirely true, of course, few people know what every little thing on the green circuit board does, but you have to respect the optimism.

Apple led this movement with the iMac G3. But there were many more examples.

From Whimsy to Brutalism

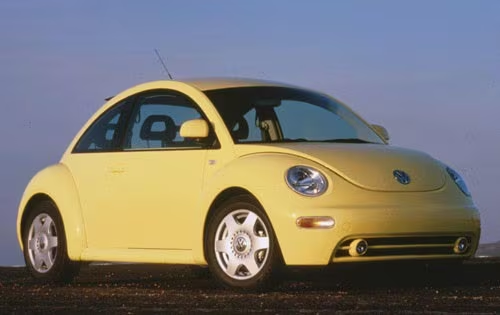

In a similar vein, the contrast between the 1998 Volkswagen New Beetle and today's Tesla Cyber truck is quite astonishing. How could the same culture have created both? The Beetle, bulbous, colourful, small and not even sporty or fast, like a Nintendo version of a car...a real like Mario Kart. Whimsical. No, not beautiful, it's...something else.

Contrast with the so-called Cyber truck, ugly–yes, I think it's ugly–confrontational, not even a colour, just bare metal, brutal, geometric and sharp-edged. It is not a fun vehicle. It is not whimsical, but it is also not serious. (And, also somehow different from the Hummer, which is the often compared strange-cousin to the New Beetle.) Not fun, or beautiful, but not serious or functional either. What is that kind of design?

This is such a clear movement from open, hopeful technology of the 1990s/2000s to opaque, imposing and inscrutable products and systems. The world has entered some kind of new phase, as we have now left behind "the end of history" and entered a strange parallel, definitely less optimistic, universe.

Invisible Computers, Transparent Computers, Blackboxes...The Paradox of Modern Computing

But the metaphor of the transparent computer breaks down pretty quickly, and is tangentially related to the idea of "invisible computers." I've talked about the idea of the "invisible computer" before, for example:

Blackbox AI

We mostly treat AI models as a black box: something goes in and a response comes out, and it's not clear why the model gave that particular response instead of another. This makes it hard to trust that these models are safe: if we don't know how they work, how do we know they won't give harmful, biased, untruthful, or otherwise dangerous responses? How can we trust that they’ll be safe and reliable? - Anthropic [4]

I've written about this previously.

At the moment we don't know what goes on inside a large language model. We have no way of reliably understanding their decision-making processes, how they come to the conclusions they do (although Anthropic has done some research in this area [4]).They really are a "black box", almost completely inscrutable.

This is an interesting comparison with the translucent computers and other products of the 2000s. Overall, the shift reflects a massive cultural, societal shift in terms of our relationship with technology. Instead of being able to see what's going on inside computers, if only the blinking lights, we're now in a situation where we're working with AI systems that are not only obtuse, but that also run in the "cloud", where the cloud is not a fun, fluffy thing, but rather a misnomer for massive, invisible mega-data centres–the antithesis of translucent computers.

Looking Forward

However, AI isn't all bad. While there are certainly dark sides to recent advances in AI, around privacy, micromanagement, global facial recognition, etc, there is potential for good as well.

- It may not remain a black box forever–at some point we may be able to understand how LLMs come to their conclusions.

- AI has the potential to make computing more fun, e.g. if we don't have to type on keyboards or look at monitors to get things done through the "computer", it has the potential to transform computing into something less like work and more like fun, for example, taking a walk in the woods.

- Using AI while ensuring personal privacy is difficult. However, we may be able to build some good solutions and perhaps legislation in this area–if we try.

- We have the potential to run local LLMs–there are open source, open weight, LLMs, some more open source than others, but they can be run locally, which will help with privacy.

No Fun?

So much of everyday life in the twenty-first century has taken on a feverish, even bizarro tinge. We’ve seen a reality TV star in the White House, the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories (from progressive fantasies about Russian kompromat to conservative paranoia about vaccines and pets in Ohio), freak weather patterns and a biosphere breakdown, mass quarantine and state-mandated mothballing of entire sectors of the economy, an angry mob encouraged to invade the U.S. Capitol by an outgoing president, and angry truckers blockading Parliament Hill and threatening to execute the prime minister. Norms have been busted, expectations scrambled. The Overton window — the measure of how long it takes on average for a fringe idea to make its way into the political mainstream — has been itself thrown out of the window. - James Brooke-Smith [1]

Geopolitics plays a big part in our subconscious, and that in turn relates to what kind of products we create–products that, as of today, on the surface at least, don't look as fun as they did in the 2000s. There was a kind of weird optimistic zeitgeist then, and it's not here now. But it could return. AI, which is currently a black box, could actually help us get back to fun products. Fun computing probably has no choice but to be human-centric.

Further Reading

[1]: https://reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2024/11/the-end-of-the-end/

[2]: https://www.harpercollins.com/products/y2k-colette-shade?variant=41231617097762

[3] - https://aesthetics.fandom.com/wiki/Y2K

[4] - https://www.anthropic.com/research/mapping-mind-language-model

[5] - https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/09/03/francis-fukuyama-postpones-the-end-of-history

[6] - https://pages.ucsd.edu/~bslantchev/courses/pdf/Fukuyama%20-%20End%20of%20History.pdf